My daddy died on Friday morning at about 7:35am. I was sitting in a chair beside his bed as his ragged breathing became slower and shallower until it finally stopped. It was a very peaceful end to a very well-lived life. We should all be so lucky.

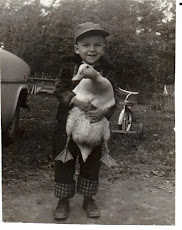

He was born in 1923 in Monmouth, Oregon, third of four children of a wild west drifter turned farmer and a Denver society girl turned farmer's wife. Some of his earliest memories were of their trek across country in 1928, moving a family of six from Oregon to the Eastern Shore of Maryland in a Model A truck. We still have a chunk of petrified wood collected from the Petrified Forest on that trip.

His stories of growing up on their farm, doing chores, building things, killing rats and being best friends with his paraplegic younger brother Jim (from whom I got my name) are well documented in two sources, both of which he wrote while in his eighties: The Big D, an unpublished manuscript describing his childhood during the Great Depression; and Pinetown, a fictional story which was published by Publish America in 2010. Both are full of stories about farm life during that period of time and in that place, including a richly detailed account of the operation of a steam powered wheat harvester. Their way of life influenced his way of life on into the twenty-first century: don't buy it if you can make it; use it until it wears out beyond usefulness; waste nothing, throw away nothing. We dealt with this until the very end.

After Gilbert graduated high school, his father tried to hand the farm over to him. He declined. He worked in a tomato canning plant, a button factory and then Glenn L. Martin's airplane factory in Baltimore at the beginning of World War II. His experience there no doubt influenced the Navy's decision to send him to airplane mechanic school before stationing him at Vero Beach Naval Air Station in Florida. He was an engine change mechanic there for the duration of the war, although they all expected to be shipped out to more exciting duty at any moment. They were the lost patrol, forgotten by the Navy bigwigs to the end. One guy was born and raised in Vero, and joined the Navy to see the world. Damn!

The best thing about Vero Beach, however was this beautiful young woman who volunteered as a coast watcher (the Japanese never attacked Vero Beach!) and at the Ship's Service Club, a community-sponsored recreation place for the sailors. Gilbert and Wynifred hit it off pretty well, though their marriage only lasted seventy years and one day, until death did them part.

They married in April of 1946, right after his discharge from the Navy, and drove from Vero Beach to the Eastern Shore of Maryland to introduce her to his family. Then they took up residence in the southern outskirts of Baltimore while Gilbert worked and went to art school. Like me, his first job was at Montgomery Ward. Unlike me, he worked in the warehouse. His first illustration job was with the Baltimore City Planning Commission. From there he moved on up to the Maryland State Roads Commission. Then he got a great gig close to the first house they owned, built from a Sears & Roebuck kit by him and his brother Bob on the lot next to brother Bob's place in Odenton, Maryland. He worked at Westinghouse Armaments Division five miles down the road, illustrating bombs, rockets, torpedoes and the like for sales materials to be shown to the military. He taught himself to airbrush over a weekend before starting that job.

We found out last month, during one of his marathon story telling sessions in our living room, that my mother badgered him into applying for the illustrator job at National Geographic. He was perfectly content to meander five miles through the countryside to Westinghouse every morning. Driving thirty five miles into the heart of Washington D.C. did not hold the same appeal, even if the prospect of working for a magazine like National G. was about as cool as it gets. But he got the job, and stayed for thirteen years. For a few years he took the train in, but as his responsibilities grew, he needed to have the flexibility of driving a car in.

In 1968, as the country reeled from the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, Gil and Wyni decided to get crazy and move to Vero Beach, where her mother still lived, and try to make a living as a free-lance commercial artist. I went into tenth grade at Vero Beach High School, while my dad worked at convincing Vero that they needed a free-lance commercial artist. Success was limited, but their shared ability to stretch whatever money came in served them well. I worked in the biz part time, and often made more money than they did.

During the 70s, after I graduated High School and went to live in Maryland, they supplemented their meager income by working real jobs. My mother worked at the library, and my dad at the VB City Planning Commission. In his free time, he threw himself into his lifelong passion for painting wildlife, and on weekends set up a booth at art shows all over Florida. Also, they bought a couple of duplexes for rental properties.

Then in the spring of 1978, I returned to Vero, and my dad and I decided to really make a go of Emerson Art Service. He bought a copy camera, we built a big darkroom for it, and we set out to conquer Vero Beach. The huge break came in the latter months of 1979. The Dodgers, who did their Spring Training at what used to be the Vero Beach Naval Air Station, were planning to start a minor league team playing in the Florida State League. They needed someone to do their programs, pocket schedules, posters and newspaper advertising. They inquired at every print shop and publication they could find. Every single one told them that Gil Emerson was the man they should deal with. After the sixth or seventh time, they surrendered, and we became graphic artists to the Dodgers. We had, by that time, several other accounts that gave us a modicum of work, but the Dodgers were our bread and butter.

Then in 1986, at the ripe old age of sixty three, Dad decided to hand the business over to me. I declined. My new wife and I moved to St. Cloud, Florida, about a hundred miles from Vero, and my dad sold the business to one of our competitors. They bought a small used motor home, and began searching the Carolinas and Georgia for a place to spend their summers away from the oppressive heat and hurricanes. Finally, in 1995, they bought a lot in the mountains of North Georgia, paid a contractor to build the foundation, outside walls, roof, sub-floors and stairs between the three floors, with enough framing inside to hold it together. A plumber plumbed the kitchen and two bathrooms, and an electrician wired the whole house, with my dad as his helper. From then until he came to live with us in Nashville, my dad worked at finishing the "cabin." It was his last great work of art.

The last three months of his life were very special to Carmen and me. We delighted in listening to his stories, we found joy in helping him with things that once were easy for him. We fixed food for him, and in the last days even spoon fed him. All the while, he was grateful to be with us instead of in a nursing home, and even was tender and loving sometimes - something he rarely was before then. We took him in knowing he would die soon, and we all made the most of our final three months together. The last week saw a sharp decline in his strength and his mental alertness. He stopped eating, couldn't produce anything on the toilet - try as he might, and several times said "Why can't I just die?!" He refused the comfort medicines provided by Hospice until Thursday night. Friday morning he was totally unfocused, confused and agitated. We gave him some medicine, he calmed down, closed his eyes and gradually stopped breathing. It was a very peaceful end with me sitting beside him. We should all be so lucky.

Tuesday, April 25, 2017

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment