My previous post came rushing out of me in a frenzy. Since publishing it, I have had a lot of time to think about what I left out of it, which is, of course, a lot. The most important part of his life well lived was his impact on the people around him.

The first huge impact he had was on his brother Jim, who was born paraplegic to a farm family, in which pulling your weight was paramount. Gilbert was my Uncle Jim's best friend to the end of Jim's life. During their childhood together, they figured out ways to include a paraplegic boy in every aspect of their life. Gilbert built transportation devices for getting him around the farm, carried him around the neighborhood on his bike, insisted on including him as plate umpire in baseball games, and helped figure out ways to make it possible for Jim to do his share of chores with some device or gadget they would invent and manufacture. In an early indication of the direction his life would take, Gilbert was the illustrator of the bird books he and Jim produced. Jim wrote the text, Gil drew the pictures. When they got mad at each other, they would each tear up their half of the bird book. Then they'd make up and start over.

During his time in the Navy, Gil was an excellent morale booster. His wacky sense of humor and upbeat attitude were just what was needed during those grim years. He did impressions of the celebrities of the day - such as Jack Benny and Rochester, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. In one instance, he hid behind the radio, which was huge enough to hide behind, and did a long Roosevelt speech which included the story of those brave men in uniform fighting the war from the little town of Vero Beach, Florida. He had them mesmerized for a short time, until he got so specific, even naming names, that they knew it wasn't really FDR.

After the war, he married Wynifred, and a year later they had their first son, Jack. My dad was a good dad to both of us, even though my mother insisted that he refrain from being affectionate so that we didn't grow up to be sissies. He was always involved in our lives, gave us baths, helped us build things, took us with him when he could. When Jack was in second grade, Gilbert became president of the PTA in Odenton Elementary. He was president when the Supreme Court handed down their decision that segregation was unconstitutional. Gil refused to consider all the mighty protests that were thrown down. He told them that he would cooperate with the decision, and if they didn't like it they could vote him out of office. They didn't.

He and my mother were largely responsible for forming a Cub Scout pack in Odenton. He was Cubmaster for many years, and my mother was a den mother for many more. One really cool thing I remember from the Cub Scout years was a thing he built for ceremonies. When he asked Akela for a sign that He was with them, an arrow suddenly appeared, stuck into a target. In later years, I realized that the arrow was inside the target, spring loaded to pop out suddenly so that it seemed as if it had been shot from beyond. Show biz.

He was always very involved in Boy Scouts. He was Scoutmaster sometimes, Assistant Scoutmaster sometimes, and went camping with us whenever his schedule permitted. My favorite adventure (and his too, I believe) was a week-long canoe trip, 87 miles down the Potomac River, sleeping under the stars on the river banks in the mountains of West Virginia and Maryland. He took a lot of pictures on Kodachrome, and after we got home and rested up, he and I created a slide show with two carousels of slides and a reel-to-reel tape with his narration and music. We presented it several times to Scouting groups in the area that were thinking about doing the same trip. We recommended it highly.

When we moved to Vero Beach, one of the services he tried to market was slide show production. We did several, most notably one for Mel Fisher, the famous seeker of sunken treasure. Is it any wonder, then, that my project for High School Communications class was a very dramatic slide show with music? Or that I was a sound technician in community theatre years before I built sets. But I digress.

One of the first big projects we did in Vero Beach was a bit of show biz. 1969, our first full year living there, was the 50th anniversary of the incorporation of the City of Vero Beach. The Indian River Citrus Bank hired us to build a full-size replica of the front of a 1919 Model T Ford for people to sit in and have their picture taken in front of a street scene of 14th Avenue as it was in 1919. At sixteen, I was in awe of his ability to transform ordinary objects into windshield, headlights, grill and radiator cap, not to mention drawing and painting the street scene. When we were done, the pictures looked for all the world like people were coming down 14th Avenue in a Model T. I was proud.

Gilbert was in business there for about twenty years. We worked together for my three years of high school, and then for nine years before I married Carmen and we moved to St. Cloud. During that time he developed a devoted pool of clients and vendors. The thing I liked best about it, however, was his willingness to take on young people with no experience in graphic art (me being the first) and teach them the business. He preferred people who had no formal art schooling, because he didn't have to deal with the know-it-all attitude. He could teach them what he needed them to know how to do, and they were grateful for it. Most notably, my friend Craig, a brilliant guitar player and singer. His family was always struggling, due to the sketchy opportunities for brilliant musicians in the little city. But I knew that he also could draw. The thing that told me that he was a good candidate for the Gil Emerson School of Art was the fake license plate expiration sticker he put over his expired sticker. I had to get very close to it to see that it was hand drawn. I brought him in in '82, and he stayed with my dad until a year or so after I left in '87. Craig and his family also lived in one of Gil and Wyni's rental properties for nearly twenty years, their longest stay in any one dwelling.

The rental properties were another matter. For one thing, helping him with repairs and maintenance taught me a lot (mostly it taught me to not be a landlord) and for another, it was a platform from which to help people along. Sure, he got screwed now and then, but there's a much longer list of families who are forever grateful to him and my mother for their compassion and flexibility, including Craig's family.

Then they moved to Smokey Mountain Estates in Blairsville, Georgia. I am truly grateful for the help and support given to both my parents, but mostly my dad, by his neighbors on the mountain. Mary and Darrell just down the hill have been wonderful friends to them, providing companionship, gluten-free beer, dinners out and in their home, and transportation above and beyond. Ted and Ray and Chip and the rest have all been helpful and fun to have around. I personally attended the 70th anniversary party, which provided us a brief respite from a long siege with my mother in the hospital; and the Goodbye Gil party in February, with Gil Emerson wildlife paintings as party favors for the guests to take home. Both parties featured live entertainment, as well as story telling, gifts and good wishes.

And let us not forget Rachel. She married my brother in 1986, divorced him ten years later, but remained the devoted daughter-in-law for as long as my parents lived, which was thirteen years beyond the death of my brother. In 2013, six months after Gil's stroke, she moved from Denver to Blairsville to be there for my parents. Living in their house quickly became impossible with my mother's dementia, but she got an apartment nearby and continued to help them out with whatever they would let her do. It was a great comfort to us to have her there, and to my dad as well. Luckily, she still loves living in Blairsville.

Anyhoo, perhaps you can tell that the biggest impact he had on anybody, was on me. From him I got my patience and calm demeanor, my love of inventing and building interesting things, my facility with sound technology and my wacky sense of humor. All of those attributes have served me well over the years and decades. And the long history of doing things as a team served us both well as we navigated life together as hospice patient and care giver.

The Wizard of Oz said, "A heart isn't measured by how much you love, but by how much you are loved by others." My daddy had a huge heart.

Tuesday, May 9, 2017

Tuesday, April 25, 2017

Gilbert H. Emerson: A Life Well Lived

My daddy died on Friday morning at about 7:35am. I was sitting in a chair beside his bed as his ragged breathing became slower and shallower until it finally stopped. It was a very peaceful end to a very well-lived life. We should all be so lucky.

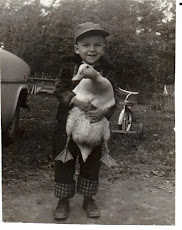

He was born in 1923 in Monmouth, Oregon, third of four children of a wild west drifter turned farmer and a Denver society girl turned farmer's wife. Some of his earliest memories were of their trek across country in 1928, moving a family of six from Oregon to the Eastern Shore of Maryland in a Model A truck. We still have a chunk of petrified wood collected from the Petrified Forest on that trip.

His stories of growing up on their farm, doing chores, building things, killing rats and being best friends with his paraplegic younger brother Jim (from whom I got my name) are well documented in two sources, both of which he wrote while in his eighties: The Big D, an unpublished manuscript describing his childhood during the Great Depression; and Pinetown, a fictional story which was published by Publish America in 2010. Both are full of stories about farm life during that period of time and in that place, including a richly detailed account of the operation of a steam powered wheat harvester. Their way of life influenced his way of life on into the twenty-first century: don't buy it if you can make it; use it until it wears out beyond usefulness; waste nothing, throw away nothing. We dealt with this until the very end.

After Gilbert graduated high school, his father tried to hand the farm over to him. He declined. He worked in a tomato canning plant, a button factory and then Glenn L. Martin's airplane factory in Baltimore at the beginning of World War II. His experience there no doubt influenced the Navy's decision to send him to airplane mechanic school before stationing him at Vero Beach Naval Air Station in Florida. He was an engine change mechanic there for the duration of the war, although they all expected to be shipped out to more exciting duty at any moment. They were the lost patrol, forgotten by the Navy bigwigs to the end. One guy was born and raised in Vero, and joined the Navy to see the world. Damn!

The best thing about Vero Beach, however was this beautiful young woman who volunteered as a coast watcher (the Japanese never attacked Vero Beach!) and at the Ship's Service Club, a community-sponsored recreation place for the sailors. Gilbert and Wynifred hit it off pretty well, though their marriage only lasted seventy years and one day, until death did them part.

They married in April of 1946, right after his discharge from the Navy, and drove from Vero Beach to the Eastern Shore of Maryland to introduce her to his family. Then they took up residence in the southern outskirts of Baltimore while Gilbert worked and went to art school. Like me, his first job was at Montgomery Ward. Unlike me, he worked in the warehouse. His first illustration job was with the Baltimore City Planning Commission. From there he moved on up to the Maryland State Roads Commission. Then he got a great gig close to the first house they owned, built from a Sears & Roebuck kit by him and his brother Bob on the lot next to brother Bob's place in Odenton, Maryland. He worked at Westinghouse Armaments Division five miles down the road, illustrating bombs, rockets, torpedoes and the like for sales materials to be shown to the military. He taught himself to airbrush over a weekend before starting that job.

We found out last month, during one of his marathon story telling sessions in our living room, that my mother badgered him into applying for the illustrator job at National Geographic. He was perfectly content to meander five miles through the countryside to Westinghouse every morning. Driving thirty five miles into the heart of Washington D.C. did not hold the same appeal, even if the prospect of working for a magazine like National G. was about as cool as it gets. But he got the job, and stayed for thirteen years. For a few years he took the train in, but as his responsibilities grew, he needed to have the flexibility of driving a car in.

In 1968, as the country reeled from the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, Gil and Wyni decided to get crazy and move to Vero Beach, where her mother still lived, and try to make a living as a free-lance commercial artist. I went into tenth grade at Vero Beach High School, while my dad worked at convincing Vero that they needed a free-lance commercial artist. Success was limited, but their shared ability to stretch whatever money came in served them well. I worked in the biz part time, and often made more money than they did.

During the 70s, after I graduated High School and went to live in Maryland, they supplemented their meager income by working real jobs. My mother worked at the library, and my dad at the VB City Planning Commission. In his free time, he threw himself into his lifelong passion for painting wildlife, and on weekends set up a booth at art shows all over Florida. Also, they bought a couple of duplexes for rental properties.

Then in the spring of 1978, I returned to Vero, and my dad and I decided to really make a go of Emerson Art Service. He bought a copy camera, we built a big darkroom for it, and we set out to conquer Vero Beach. The huge break came in the latter months of 1979. The Dodgers, who did their Spring Training at what used to be the Vero Beach Naval Air Station, were planning to start a minor league team playing in the Florida State League. They needed someone to do their programs, pocket schedules, posters and newspaper advertising. They inquired at every print shop and publication they could find. Every single one told them that Gil Emerson was the man they should deal with. After the sixth or seventh time, they surrendered, and we became graphic artists to the Dodgers. We had, by that time, several other accounts that gave us a modicum of work, but the Dodgers were our bread and butter.

Then in 1986, at the ripe old age of sixty three, Dad decided to hand the business over to me. I declined. My new wife and I moved to St. Cloud, Florida, about a hundred miles from Vero, and my dad sold the business to one of our competitors. They bought a small used motor home, and began searching the Carolinas and Georgia for a place to spend their summers away from the oppressive heat and hurricanes. Finally, in 1995, they bought a lot in the mountains of North Georgia, paid a contractor to build the foundation, outside walls, roof, sub-floors and stairs between the three floors, with enough framing inside to hold it together. A plumber plumbed the kitchen and two bathrooms, and an electrician wired the whole house, with my dad as his helper. From then until he came to live with us in Nashville, my dad worked at finishing the "cabin." It was his last great work of art.

The last three months of his life were very special to Carmen and me. We delighted in listening to his stories, we found joy in helping him with things that once were easy for him. We fixed food for him, and in the last days even spoon fed him. All the while, he was grateful to be with us instead of in a nursing home, and even was tender and loving sometimes - something he rarely was before then. We took him in knowing he would die soon, and we all made the most of our final three months together. The last week saw a sharp decline in his strength and his mental alertness. He stopped eating, couldn't produce anything on the toilet - try as he might, and several times said "Why can't I just die?!" He refused the comfort medicines provided by Hospice until Thursday night. Friday morning he was totally unfocused, confused and agitated. We gave him some medicine, he calmed down, closed his eyes and gradually stopped breathing. It was a very peaceful end with me sitting beside him. We should all be so lucky.

He was born in 1923 in Monmouth, Oregon, third of four children of a wild west drifter turned farmer and a Denver society girl turned farmer's wife. Some of his earliest memories were of their trek across country in 1928, moving a family of six from Oregon to the Eastern Shore of Maryland in a Model A truck. We still have a chunk of petrified wood collected from the Petrified Forest on that trip.

His stories of growing up on their farm, doing chores, building things, killing rats and being best friends with his paraplegic younger brother Jim (from whom I got my name) are well documented in two sources, both of which he wrote while in his eighties: The Big D, an unpublished manuscript describing his childhood during the Great Depression; and Pinetown, a fictional story which was published by Publish America in 2010. Both are full of stories about farm life during that period of time and in that place, including a richly detailed account of the operation of a steam powered wheat harvester. Their way of life influenced his way of life on into the twenty-first century: don't buy it if you can make it; use it until it wears out beyond usefulness; waste nothing, throw away nothing. We dealt with this until the very end.

After Gilbert graduated high school, his father tried to hand the farm over to him. He declined. He worked in a tomato canning plant, a button factory and then Glenn L. Martin's airplane factory in Baltimore at the beginning of World War II. His experience there no doubt influenced the Navy's decision to send him to airplane mechanic school before stationing him at Vero Beach Naval Air Station in Florida. He was an engine change mechanic there for the duration of the war, although they all expected to be shipped out to more exciting duty at any moment. They were the lost patrol, forgotten by the Navy bigwigs to the end. One guy was born and raised in Vero, and joined the Navy to see the world. Damn!

The best thing about Vero Beach, however was this beautiful young woman who volunteered as a coast watcher (the Japanese never attacked Vero Beach!) and at the Ship's Service Club, a community-sponsored recreation place for the sailors. Gilbert and Wynifred hit it off pretty well, though their marriage only lasted seventy years and one day, until death did them part.

They married in April of 1946, right after his discharge from the Navy, and drove from Vero Beach to the Eastern Shore of Maryland to introduce her to his family. Then they took up residence in the southern outskirts of Baltimore while Gilbert worked and went to art school. Like me, his first job was at Montgomery Ward. Unlike me, he worked in the warehouse. His first illustration job was with the Baltimore City Planning Commission. From there he moved on up to the Maryland State Roads Commission. Then he got a great gig close to the first house they owned, built from a Sears & Roebuck kit by him and his brother Bob on the lot next to brother Bob's place in Odenton, Maryland. He worked at Westinghouse Armaments Division five miles down the road, illustrating bombs, rockets, torpedoes and the like for sales materials to be shown to the military. He taught himself to airbrush over a weekend before starting that job.

We found out last month, during one of his marathon story telling sessions in our living room, that my mother badgered him into applying for the illustrator job at National Geographic. He was perfectly content to meander five miles through the countryside to Westinghouse every morning. Driving thirty five miles into the heart of Washington D.C. did not hold the same appeal, even if the prospect of working for a magazine like National G. was about as cool as it gets. But he got the job, and stayed for thirteen years. For a few years he took the train in, but as his responsibilities grew, he needed to have the flexibility of driving a car in.

In 1968, as the country reeled from the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, Gil and Wyni decided to get crazy and move to Vero Beach, where her mother still lived, and try to make a living as a free-lance commercial artist. I went into tenth grade at Vero Beach High School, while my dad worked at convincing Vero that they needed a free-lance commercial artist. Success was limited, but their shared ability to stretch whatever money came in served them well. I worked in the biz part time, and often made more money than they did.

During the 70s, after I graduated High School and went to live in Maryland, they supplemented their meager income by working real jobs. My mother worked at the library, and my dad at the VB City Planning Commission. In his free time, he threw himself into his lifelong passion for painting wildlife, and on weekends set up a booth at art shows all over Florida. Also, they bought a couple of duplexes for rental properties.

Then in the spring of 1978, I returned to Vero, and my dad and I decided to really make a go of Emerson Art Service. He bought a copy camera, we built a big darkroom for it, and we set out to conquer Vero Beach. The huge break came in the latter months of 1979. The Dodgers, who did their Spring Training at what used to be the Vero Beach Naval Air Station, were planning to start a minor league team playing in the Florida State League. They needed someone to do their programs, pocket schedules, posters and newspaper advertising. They inquired at every print shop and publication they could find. Every single one told them that Gil Emerson was the man they should deal with. After the sixth or seventh time, they surrendered, and we became graphic artists to the Dodgers. We had, by that time, several other accounts that gave us a modicum of work, but the Dodgers were our bread and butter.

Then in 1986, at the ripe old age of sixty three, Dad decided to hand the business over to me. I declined. My new wife and I moved to St. Cloud, Florida, about a hundred miles from Vero, and my dad sold the business to one of our competitors. They bought a small used motor home, and began searching the Carolinas and Georgia for a place to spend their summers away from the oppressive heat and hurricanes. Finally, in 1995, they bought a lot in the mountains of North Georgia, paid a contractor to build the foundation, outside walls, roof, sub-floors and stairs between the three floors, with enough framing inside to hold it together. A plumber plumbed the kitchen and two bathrooms, and an electrician wired the whole house, with my dad as his helper. From then until he came to live with us in Nashville, my dad worked at finishing the "cabin." It was his last great work of art.

The last three months of his life were very special to Carmen and me. We delighted in listening to his stories, we found joy in helping him with things that once were easy for him. We fixed food for him, and in the last days even spoon fed him. All the while, he was grateful to be with us instead of in a nursing home, and even was tender and loving sometimes - something he rarely was before then. We took him in knowing he would die soon, and we all made the most of our final three months together. The last week saw a sharp decline in his strength and his mental alertness. He stopped eating, couldn't produce anything on the toilet - try as he might, and several times said "Why can't I just die?!" He refused the comfort medicines provided by Hospice until Thursday night. Friday morning he was totally unfocused, confused and agitated. We gave him some medicine, he calmed down, closed his eyes and gradually stopped breathing. It was a very peaceful end with me sitting beside him. We should all be so lucky.

Sunday, February 12, 2017

Both Sides Now - Reflections On Daddyhood

Most of my dedicated fans know that my 93-year-old father finally decided that he couldn't hack it any longer, living alone in a three story house on the side of a mountain. He came to live with us on my 64th birthday, January 12th, 2017. Carmen gave up her office; it's now my dad's room. He says it's the finest private nursing home he's ever seen.

He has a laundry list of health issues: celiac disease, emphysema, extreme difficulty swallowing and abysmal balance. He has fallen several times since coming here. Thankfully, we have caught him most of the time. He has bad dentures that don't help him chew, so his food is nearly always soft or blenderized, and his allergy to wheat and gluten narrows the choices of foods quite a bit. He's 5'10" and 95 pounds, and losing weight.

For the most part, his spirits are good, and he loves to talk. He likes to tell his stories of his childhood on the farm during the 1930s, his WWII Navy experiences, his working life at the Baltimore City Planning Dept., the Maryland State Roads Commission, Westinghouse Armaments Division and The National Geographic Society. He was an illustrator at heart when he was eight years old, and continued to draw and paint for a living - or at least a supplement - until his stroke in 2013. He didn't lose much, as strokes go, but he forgot how to draw and paint. He also lost the ability to read and make sense of sentences and paragraphs. He can read the words, but not tie them together into complex thoughts. And his hearing is very bad. Lucky for him, I dealt with a very hard of hearing mother for fifty years or more, so I know how to make myself heard.

It's now pretty much up to Carmen and me - mostly me - to keep his life together, make sure he has food he can eat, keep his bills and accounts up to date, get him to appointments on time and with the proper paperwork, wash his clothes and his dishes, and be his ears and his memory. Basically, I'm his daddy now. But that's okay. He was my daddy for a very long time.

He has a laundry list of health issues: celiac disease, emphysema, extreme difficulty swallowing and abysmal balance. He has fallen several times since coming here. Thankfully, we have caught him most of the time. He has bad dentures that don't help him chew, so his food is nearly always soft or blenderized, and his allergy to wheat and gluten narrows the choices of foods quite a bit. He's 5'10" and 95 pounds, and losing weight.

For the most part, his spirits are good, and he loves to talk. He likes to tell his stories of his childhood on the farm during the 1930s, his WWII Navy experiences, his working life at the Baltimore City Planning Dept., the Maryland State Roads Commission, Westinghouse Armaments Division and The National Geographic Society. He was an illustrator at heart when he was eight years old, and continued to draw and paint for a living - or at least a supplement - until his stroke in 2013. He didn't lose much, as strokes go, but he forgot how to draw and paint. He also lost the ability to read and make sense of sentences and paragraphs. He can read the words, but not tie them together into complex thoughts. And his hearing is very bad. Lucky for him, I dealt with a very hard of hearing mother for fifty years or more, so I know how to make myself heard.

It's now pretty much up to Carmen and me - mostly me - to keep his life together, make sure he has food he can eat, keep his bills and accounts up to date, get him to appointments on time and with the proper paperwork, wash his clothes and his dishes, and be his ears and his memory. Basically, I'm his daddy now. But that's okay. He was my daddy for a very long time.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)